Container Driven Development

Revolutionizing software development one box at a time

Three important technological trends are causing seismic shifts in the way we develop and deliver software. These trends are:

- The rise of cloud-based computing: Through the use of virtualization and intelligently defined application programming interfaces, it is nearly effortless to deploy computing resources designed to tackle difficult problems.

- The adoption of microservice architectures: By placing the emphasis on small programs that focus on doing one thing well and combining those programs into larger units to deliver more complex functionality, it is possible to create sophisticated systems while increasing the pace of development.

- The emergence of DevOps practices allows companies to be more innovative and compete more effectively:

DevOps is a "combination of tools, practices, and philosophies that increase an organization's ability to deliver applications and services at high velocity..."

- Amazon

While each individual trend has caused disruption in the tech industry, their convergence in the form of containers is where the greatest shakeup has occurred. In this article we'll look at some of the reasons why. We'll delve into the challenges that containers solve, the current state of the art, and the broader ecosystem which has evolved around them.

What Container-Driven Development Enables

- Containers turn "it works on my machine" into a solvable engineering problem. When you build and run inside a container, you eliminate environment drift, start from a known point, and make releases more reliable.

- Docker is a workflow layer, OCI runtimes are the execution layer.

- Modern container platforms are about systems, not single containers: pods, pipelines, and repeatable environments.

Rise of Container Development

Container driven development is a development workflow that writes, runs, and tests code inside a containerized environment. A container is a portable packaged file that contains an application (often structured as a microservice) along with its source code, libraries, assets, and any other dependencies required to execute properly.

The idea of simplifying a complex application down to a container provides a number of benefits. These benefits include:

- consistent deployment and execution

- application portability where the same artifact can be used in development, staging, and production

- ways to store, transport, and deploy applications across a variety of runtimes

Containers solve a number of challenges in software development. In a traditional workflow, development would consist of writing the program, building the system, testing the resulting artifacts, and then packaging the components in such a way that they can be deployed. Many steps in the process often require manual processes that can be time-consuming and prone to error.

Benefits of Using Containers for Development

The usage of containers remedies many problems by bringing a degree of formality to the build and packaging of the application, creating a single artifact that can be used for testing, and providing a consistent artifact that can be used in development, staging, and production. Because the entire process provides parity to where the program will be deployed, issues and bugs related to differences in environment are minimized. Additionally, automated processes can be built around the build, testing, and deployment; which allows for software to be released at a faster rate.

Isolation

Containers virtualize CPU, memory, storage, and network resources at the OS-level. Processes running inside one container are not visible to processes running inside of another. This provides two major benefits: sensitive processes can be isolated into one logical sandbox, invisible to other processes running on the machine. Additionally, the logical isolation provides developers with a sandboxed view of an OS that is isolated from other software which might also be deployed. This isolation helps simplify the runtime environment and prevent unintended interactions between similar applications that might be using the same host.

Start from a Clean (Runtime) Slate

A common cause of software bugs is differences in environment. A developer may have one set of dependencies installed on a local workstation (often accumulated through months or years of working on an application), staging may have a slightly different set, and production a third set. Additionally, when code is executed, cache files are generated and become part of the environment and may contribute to subtle interactions that cause difficult-to-diagnose bugs.

Due to the way containers are built and deployed, they always begin their execution from a consistent starting point. When the container is terminated and removed, runtime artifacts are removed on cleanup. The process works consistently in development, staging, and production; greatly reducing the likelihood of "deep bugs."

Consistent, Well-Defined Environments

While containers and their template images can be created interactively by committing changes as an image, it is far more common to build them using a recipe called a Dockerfile. Dockerfiles can reference other container images (called base images) and then extend them with additional configuration and components. Because the file contains the exact specification of the container, it is possible to certify that all images built from the same Dockerfile will function identically. Images can be versioned, which means that it is possible to precisely define the components of a complex application spanning multiple containers and ensure that all components work as expected.

Building new container images is often automated and tied to events such as code check-in. This allows for the creation of larger processes, such as continuous integration and deployment pipelines, that can greatly speed up the deployment of new software versions after they have been rigorously tested.

Delivery and Deployment

Container-native development not only improves developer productivity, but also helps organizations standardize operations and processes. When applications are packaged in containers, it becomes much easier for operations teams to move a tested and verified program version to staging, and then on to production. The startup and entry for each container is consistent, meaning you know the container will initialize, allocate resources, pass configuration values, and manage artifacts the same way every time. This makes it possible to automate key portions of the deployment pipeline, and can allow for software to be released quickly (perhaps even multiple, or dozens of times per day).

The Evolution of Containers

Container technologies build upon a long history of improvements in software packaging and process isolation

Challenges of Packaging Software

Historically, software was provided as source files which needed to be compiled before they could be used. To install a new program, a user needed to:

- Retrieve an archive of source files

- Extract the files and generate a build configuration (for Unix systems using autotools, this was typically done by running

./configure) - Run the generated

Makefile (make) - Install the resulting software build

make install

This procedure worked well for simple software, but for larger programs with a number of dependencies, the process could be very difficult. Issues such as missing resource files or incompatibilities between software versions might require hours or even days to resolve.

Package Managers: Isolating and Mapping Dependencies

Packages were invented to combat this complexity and represented one of the first steps in software management and dependency isolation. They also provide the foundation for container environments. A package is an archive that has binaries of software, configuration, files, and dependency information. Inside each package there is metadata that contains information about the software's name, description, version number, vendor, and dependencies that are necessary for the program to install and run correctly. The binaries included in a package are compiled by maintainers of large systems and are usually tested before distribution to ensure that the environment is "sane." In a well packaged environment, software tends to "just work."

Many operating systems and programming languages come with package managers. Package Managers (PMs) automate the process of installing packages and resolving dependencies and managing software versions. They provide the foundation of creating a runtime environment. However, despite their sophistication and role in modern software ecosystems, they are limited when compared to containers (which build upon their model). One shortcoming that containers address, for example, is allowing multiple applications to share common components.

Applications often rely on the same library but use different versions, which makes it tricky to package shared libraries. While sharing dependencies is desired to keep the footprint of the platform small, it can cause conflicts requiring programs that consume the library to each include a copy, greatly increasing the size of install. When shared outside of a container, upgrading a dependency on one library could have destructive effects on others. If such a dependency issue arises, the resulting environment conflicts can be painful and very time consuming to fix.

Containers solve this problem by allowing each container image to have its own set of dependencies (when needed), and share lower-level base images when possible. This simultaneously keeps the install size small, while also allowing for custom versions of the libraries as needed.

Virtualization: Isolated Runtime Environments

One of the next significant steps toward isolated software environments came in the form of virtualization. In a virtualized system, hardware is emulated by software. This means that a single physical machine can run dozens or hundreds of "virtual machines" or "virtual appliances" each one with its own software stack. This approach solves many of the problems that can arise from running different versions of a program on a single machine. Virtualization allows for the isolation of dependencies and processes, effectively creating miniature "appliances" that can be built and deployed across a cluster of physical machines.

Unfortunately, while virtualization introduces many benefits, it also comes with a performance penalty. Each virtual machine has its own kernel, memory allocation, and init system. Because the CPU has a layer of virtualized instruction passing (or in some cases emulation), there is overhead when executing on the underlying hypervisor. While good for consistency and isolation, and an effective way to manage complexity; virtualization is not terribly efficient.

Containers extended the virtualization model by keeping many of its benefits (such providing network as a software service), but sharing the underlying kernel and init components. This removes much of the overhead, allowing for many more processes to be run on the same hardware. A powerful hypervisor is capable of running hundreds of virtual machines, but tens of thousands of container processes.

Control Groups: Foundation of Linux Containers

A second significant step toward the goal of running isolated processes within a single kernel took a major step forward in the early 2000s, in the form of zoning. Zoning allowed the system to limit a process scope to a specific set of resources. With a zone, it was possible to give an application user, process, and file system space, along with restricted access to the system hardware. Just as importantly, though, it was possible to limit the application's visibility into other parts of the system. Essentially, a process could only see those things within its own zone.

While the initial implementation of zoning was powerful, it failed to gain broad adoption until a second implementation (called "control groups" or "cgroups") became available in the Linux kernel in 2008. The project, broadly called Linux Containers (LXC), provided a kernel extension as a way for multiple isolated Linux environments (containers) to run on a shared Linux kernel, with each container having its own process and network space.

Orchestration

While cgroups provided the foundation, though, they were difficult to utilize. In 2013, Google contributed a set of utilities to an open-sourced project called Let Me Contain That For You (LMCTFY) that attempted to simplify the utilization of containers by making them easier to build and deploy. This project provided a library that could be used by applications to allow containerization through commands and a standard interface, allowing a limited degree of "orchestration."

Even this failed to gain broad adoption, though, because there was no standard way to package, transport, or deploy container components. Even with the improvements that LMCTFY provided, the process was too difficult. This started to change in 2013 with the emergence of a new utility called Docker.

Tooling and Technologies

From kernel primitives to software delivery.

Linux Containers

Linux containers are not a single tool or product—they are a set of operating system–level primitives that work together to isolate processes, manage resources, and provide repeatable execution environments. At their core, containers leverage native Linux features to create lightweight, isolated runtimes that behave like independent systems while sharing the same host kernel.

This model differs fundamentally from traditional virtual machines. Rather than virtualizing hardware, Linux containers virtualize process environments. Namespaces define what a process can see, control groups regulate how many resources it can consume, and security mechanisms constrain what it is allowed to do. Together, these capabilities enable multiple applications to run side by side on the same host with strong isolation, predictable performance, and minimal overhead.

Because these mechanisms are part of the Linux kernel itself, containers are inherently efficient and portable. They form the execution substrate on which higher-level container tooling is built, and they are the reason containers can run consistently across laptops, servers, cloud platforms, and edge devices. Everything that follows—images, registries, orchestration, and CI/CD—ultimately depends on these Linux runtime foundations.

Resource Management

While technically a feature of control groups, containers provides an interface which allows for resource constraints to be applied to a container. This can be used to specify how much memory, CPU, or other specialty resources (such as GPU) can be consumed by the program running in the container. Managing resources allows for many benefits during development: it provides a way to simulate a specialty target environment (such as might be found in an embedded device) with high fidelity, or ensuring that a greedy program doesn't hog the resources of a developer's personal laptop.

Consistency and Portability Leads to Improved Productivity

Because of their consistency and portability, containers are easy to integrate into many development workflows. For developers building an application that require supporting components (such as database, message queue, or backing microservices), creating linked containers that provide the associated systems is easy. Similarly, it is also straightforward to create a development environment within a container that mimics the production target and allows developers to mount local source files into that for work. With standardized/repeatable development, build, test, and production environments, you can rely on your containers to do what they are supposed to do every time and still provide convenient development access.

Continuous Integration and Deployment

When development occurs in a container environment, the entire lifecycle of the application can be production-parallel. This means there is often a straight shot from the time an issue is fixed to deployment. Continuous integration and continuous deployment (CI/CD) is a popular DevOps practice of automating the application build, testing, staging, and deployment processes. Many CI/CD pipelines utilize containers at their core.

Portability

One of Docker's major contributions to the container landscape came in the form of how it builds and stores images. A container image contains the environment, dependencies, and configuration required to run a program as part of a read-only file system. The image itself is built up from a series of layers, where each layer represents an instruction (usually provided as a line in Dockerfile) and the results of its execution. Each layer in an image uses a copy-on-write (COW) strategy for storing changes. This allows files to be shared between all layers of the image and provides an efficient way to capture differences. The Docker layer format has become a standard for containers (described in the OCI Image Format Specification), and gives machines a quick way to exchange images between themselves or between storage servers called registries.

This gives container images great portability. Services like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud Platform (GCP), and Microsoft Azure have embraced Docker and created managed services around it. These include managed Kubernetes (EKS, GKE, and AKS) and secure registries. Unlike other cloud services, where they may be strong vendor-specific lock-in, a container running in an Amazon Kubernetes instance can easily be ported to run within the Google, Azure, or on-premise equivalent.

Moving container images is a simple command. Using a container ID, it's possible to push a container image to any registry to which the machine or user has access. Registries can be mirrored and incorporated into workflows around deployment, security, or compliance auditing. The image format includes the ability to associate metadata and version tags, so it is possible to track changes and use the build system to troubleshoot bugs.

The stack diagram stack illustrates how container execution is composed from clearly defined layers, each with a distinct responsibility. At the bottom, the host operating system provides the kernel primitives that make containers possible. Namespaces isolate process visibility (process IDs, networking, mounts, and hostnames), while control groups (cgroups) enforce resource limits such as CPU, memory, and device access. Networking and storage subsystems provide the underlying connectivity and persistence mechanisms used by containers.

Above the kernel sits the OCI-compliant container runtime, which is responsible for turning container images into running processes. Components such as containerd and runc implement the OCI specifications, handling container lifecycle management, execution, and isolation while remaining portable across environments. This runtime layer is intentionally standardized, enabling the same container images to run consistently across different platforms.

On top of the runtime, higher-level tooling defines intent. Developer-facing tools interact with the runtime through well-defined APIs, describing what should run, how it should be configured, and which resources it should use. This separation between intent and execution is what allows containers to scale from local development to production systems without changing the underlying application.

Docker

Docker sits above the Linux container runtime as a comprehensive development and workflow toolset. Its primary contribution is not the invention of containers themselves, but the creation of a cohesive, accessible interface for building, running, and sharing containerized applications.

As a developer and CI interface, Docker brings together multiple capabilities that streamline the container lifecycle. Tools such as BuildKit enable efficient, reproducible image builds. Docker Compose provides a declarative way to define multi-container applications for local development and testing. Integrated registries make it straightforward to store, version, distribute, and audit container images across teams and environments.

Crucially, Docker abstracts the complexity of the underlying runtime. Developers interact with a small, consistent set of commands while Docker translates that intent into OCI-compliant images and runtime operations. This allows teams to focus on application behavior rather than kernel mechanics, without sacrificing portability or correctness.

In modern workflows, Docker functions as the connective tissue between development, CI pipelines, and production platforms. Images built locally can be tested unchanged in automated pipelines and deployed to Kubernetes, cloud services, or on-premise infrastructure. By standardizing how applications are packaged and handed off, Docker reduces environment drift, accelerates onboarding, and enables reliable delivery across the entire software lifecycle.

Docker as a Development Platform

Docker is best understood not as a container runtime, but as an ecosystem of developer and automation tools built on top of Linux containers and OCI standards. Its primary contribution is the unification of image building, container execution, composition, and distribution into a cohesive workflow that spans local development, continuous integration, and deployment.

By abstracting the complexity of container runtimes and kernel primitives behind consistent interfaces, Docker enables developers and CI systems to describe what should run rather than how it should be executed. This focus on intent—expressed through commands, configuration files, and images—is what makes Docker a foundational tool in modern container-driven development.

Client

The Docker Client is the primary interface through which users and automation interact with the Docker ecosystem. Most commonly accessed via the command-line interface (CLI), the client allows developers to build images, run containers, define networks and volumes, and inspect or manage local and remote resources.

Under the hood, the Docker Client communicates with the Docker Engine through a versioned REST API. This API-driven design allows Docker to integrate cleanly with CI/CD systems, IDEs, and other automation tools, ensuring that the same workflows used on a developer’s laptop can be executed consistently in build pipelines and production environments.

Because the client is decoupled from the runtime implementation, Docker commands remain stable even as underlying runtimes and platforms evolve—an important factor in Docker’s long-term adoption and ecosystem resilience.

Engine/Server

The Docker Engine is the server-side component responsible for translating developer intent into concrete runtime actions. It is typically deployed as a system daemon (dockerd) and exposes the REST API consumed by the Docker Client and other tools.

The engine orchestrates the container lifecycle by coordinating image builds, image transfers, container creation, network configuration, volume management, and resource allocation. Rather than executing containers directly, Docker Engine delegates low-level execution to an OCI-compliant runtime, most commonly containerd, which in turn uses runc to start and isolate processes.

This separation of responsibilities allows Docker to focus on workflow orchestration and developer experience while relying on standardized runtimes for execution. It also ensures that containers built with Docker can run consistently across environments that share the same OCI runtime foundations.

Registry

A Docker Registry is a service for storing, versioning, and distributing container images. Registries may be public or private and are accessed using the same Docker Client and APIs that manage local images.

Docker operates a public registry, Docker Hub, which hosts thousands of curated and community-maintained images ranging from base operating systems to databases, application servers, and development tools. In addition to public images, organizations frequently deploy private registries to support internal workflows, enforce access controls, and integrate security or compliance checks.

Because container images follow the OCI Image Format, registries are interoperable across platforms and vendors. Images can be mirrored, scanned, signed, and promoted through environments as part of automated delivery pipelines. This makes registries a central component of container-based workflows, enabling traceability, reproducibility, and controlled distribution of software artifacts.

Dive Deeper: Containers in Real Workflows

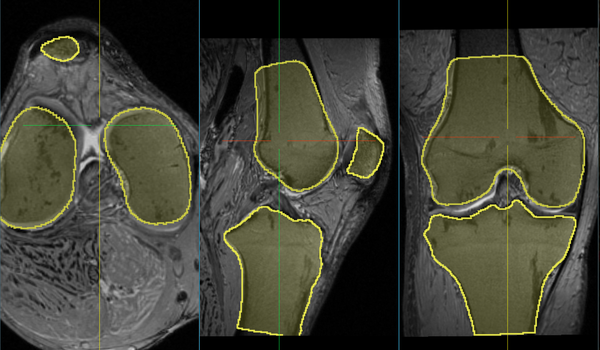

Containers aren't just a packaging format, they're a repeatable way to assemble full environments. The links below show the progression from a general-purpose data lab (storage + compute + streaming) to an integrated medical imaging platform (PACS + viewer + analytics) built on the same Docker-first workflow.

Podman: Security-First Containers

While Docker remains the most widely used container tooling ecosystem, it is not the only approach to running containers nor is it always the best fit for security-sensitive environments. Podman emerged to address a class of concerns that stem from Docker’s original architectural assumptions, particularly around privilege boundaries, daemon-based control, and attack surface.

Podman is part of a broader ecosystem of tools designed around daemonless, rootless container execution and tight integration with Linux security mechanisms. Rather than replacing containers or container images, Podman builds directly on OCI standards and Linux runtime primitives, offering a different operational and security posture while remaining compatible with existing container workflows.

Security Model: Eliminating the Privileged Daemon

One of Podman’s defining characteristics is its daemonless architecture. Unlike Docker, which relies on a long-running, privileged daemon (dockerd) to manage container lifecycle operations, Podman executes containers directly as child processes of the calling user.

This design has important security implications:

- No central root-privileged control plane. Compromising a Podman-managed container does not imply control over a long-running root daemon.

- Reduced attack surface. There is no persistent API endpoint exposed on the host for container management.

- Process ownership is explicit. Containers run as regular user processes, inheriting user identity and permissions.

In practice, this aligns containers more closely with traditional Unix process isolation models while preserving the benefits of containerization.

Rootless Containers and Least Privilege

Podman was designed from the outset to support rootless containers. Containers can be created, run, and managed entirely without administrative privileges, relying on user namespaces, subordinate UID/GID mappings, and kernel isolation features.

This enables:

- Strong least-privilege execution for development and production workloads

- Safer multi-tenant environments on shared systems

- Better alignment with hardened security policies and compliance requirements

Rootless containers also eliminate an entire class of privilege-escalation risks that arise when container runtimes require root access by default.

Deep Integration with Linux Security Controls

Podman integrates tightly with native Linux security mechanisms rather than abstracting them away. This includes:

- SELinux for mandatory access control and policy enforcement

- Seccomp profiles to restrict available system calls

- Capabilities to limit privileged operations inside containers

- User namespaces for identity isolation

- Optional KVM-based isolation (via complementary tooling) when stronger boundaries are required

Because these controls are first-class concerns rather than optional add-ons, Podman is frequently used in environments where security posture matters as much as developer convenience.

containerd vs Docker vs Podman

containerd is a low-level, OCI-compliant runtime focused on executing containers, with minimal developer-facing tooling. Docker builds on the runtime to provide image builds, composition, registries, and a unified developer and CI workflow. Podman offers Docker-compatible tooling without a central daemon, running containers directly as user processes.

Compatibility With Docker

Despite its different execution model, Podman is fully OCI-compliant and Docker-image compatible. It can pull, run, and build images from standard registries, including Docker Hub and private OCI registries.

This compatibility enables gradual adoption:

- Existing Docker-based build pipelines can remain unchanged

- Development workflows can continue to use Docker tooling

- Podman can be introduced selectively in staging or production environments where stronger isolation is required

In this way, Podman complements rather than replaces Docker in many organizations.

Pods: Multi-container Applications

A pod is a lightweight grouping mechanism that allows multiple containers to run together as a single logical unit. Containers within a pod share selected Linux namespaces—such as networking and process visibility—while remaining isolated from containers outside the pod. This makes pods a natural way to model applications composed of tightly coupled components.

Rather than treating each container as a completely independent entity, pods allow related processes to be colocated and managed together. For example, an application container can share networking, configuration, and lifecycle with a helper process such as a sidecar, proxy, or logging agent. The pod becomes the boundary for scheduling, resource allocation, and operational reasoning.

This execution model aligns cleanly with existing system concepts:

- Unix process hierarchies, where related processes share a common parent and lifecycle

- System-level observability tools, which can inspect and manage pod processes using standard Linux utilities

- Modern container platforms, which treat pods as the smallest deployable unit

In Podman, containers running inside a pod appear as predictable, inspectable processes on the host. There is no hidden orchestration layer: operators can observe, debug, and manage pod workloads using familiar tools and system semantics, while still benefiting from container isolation and resource controls.

Compatibility and Pods in Practice

Podman maintains full compatibility with Docker images and registries, enabling teams to introduce it selectively where security or operational constraints matter most—often in staging or production—while leaving existing Docker-based development and CI workflows unchanged. This makes Podman a complement to Docker, not a wholesale replacement.

With support for pods as a first-class execution model, Podman simplifies deployment of multi-process applications and enables them to work together as a single unit. Containers in a pod share selected namespaces and lifecycle, mapping naturally to Unix process hierarchies and standard system tooling. The result is a multi-container application model that is easier to reason about, inspect, and operate without relying on an external orchestration layer.

Empowering Better Process and Technology

How containers operationalize modern software practices

Containers provide many compelling features for development teams. These include a unit of packaging, a unit of deployment, a unit of reuse, a unit of resource allocation, and a unit of scaling. In essence, it provides the perfect toolset of developing and deploying microservices.

Containers also provide great value to operations teams. Because they can provide many of the benefits of virtualization, but without the overhead, they provide the capacity to enable greatly improved processes. In many important ways, though, they have also shifted the thinking about how software should be developed and deployed and enabled new computing platforms.

Enabling Cloud

Containers have allowed for "cloud" computing to evolve toward greater abstraction. Taken to its most extreme, a fully abstracted cloud platform removes all details of how a program is packaged and provisioned. From a developer's perspective, it just gets executed.

Serverless Functionality

Containers are capable of providing precisely this type of computing model. Commonly called "serverless" or "Functions as a Service," such systems allow a developer to write a simple piece of code and deploy them to a function platform, which then handles the jobs of deployment, scheduling, and execution.

Open-FaaS is an open-source serverless framework that allows users to deploy their functions in containers within a Kubernetes cluster. Open-FaaS allows users to develop their application with any language (as long as the app can be containerized), and provides a standard model to handle their execution and scaling. The functions can then be combined together to enable powerful applications and pipelines.

Accelerating DevOps

DevOps is a combination of tools, practices and philosophies that increases an organization's ability to deliver applications and services at high velocity. DevOps, as practiced at most software companies, incorporates containers.

Infrastructure as Code

Infrastructure as Code is the practice of using the same tools and methods leveraged for software development in the management of infrastructure and computing resources. At a practical level, this means the application configuration will be kept in version control, analyzed, and tested.

Containers provide a concrete implementation of Infrastructure as Code. At the most basic level, Dockerfiles create application runtimes that can then be composed together through the use of orchestration manifests and deployed into cohesive resource groups. In more sophisticated scenarios, container systems are able to request specialty resources such as GPU and specialty forms of storage.

Continuous Integration / Continuous Deployment (CI/CD)

CI/CD is the practice of developing automated suites that can test, validate, stage, and deploy code. With an effective CI/CD pipeline it is possible to deliver application updates with very high frequency. Companies such as Netflix, Amazon, Etsy, and Google are often able to update a deployed system dozens of times per day.

A rich ecosystem of tools designed to enable container based CI/CD exists. Jenkins, as an example, is a CI automation tool that can automatically create containers from source code, run test suites against them to ensure their functionality, and deploy the resulting containers to a registry if they pass the tests. Spinnaker is a CD tool capable of watching a registry for updated container builds and deploying them to a staging or production cluster.

From Primitives to Production

Containers are not just a packaging format or a deployment convenience—they are a unifying execution model that connects how software is built, tested, secured, and operated. By grounding development workflows in Linux container primitives and open standards, containers turn intent into something concrete: a repeatable, inspectable unit that behaves the same across laptops, pipelines, data centers, and cloud platforms.

What makes containers transformative is not any single tool, but the ecosystem they enable. Docker lowers the barrier to entry and standardizes workflows. Podman demonstrates that security, transparency, and least privilege can be first-class concerns. OCI ensures portability and longevity. Together, these layers allow teams to evolve processes—DevOps, Infrastructure as Code, CI/CD, and serverless—without rewriting applications or surrendering control.

In the end, containers change the question from “How do we provision and manage systems?” to “How do we express and execute intent safely and repeatedly?” That shift—away from infrastructure as an obstacle and toward execution as a capability—is what makes containers foundational to modern software delivery, not just another tool in the stack.

Comments

Loading

No results found